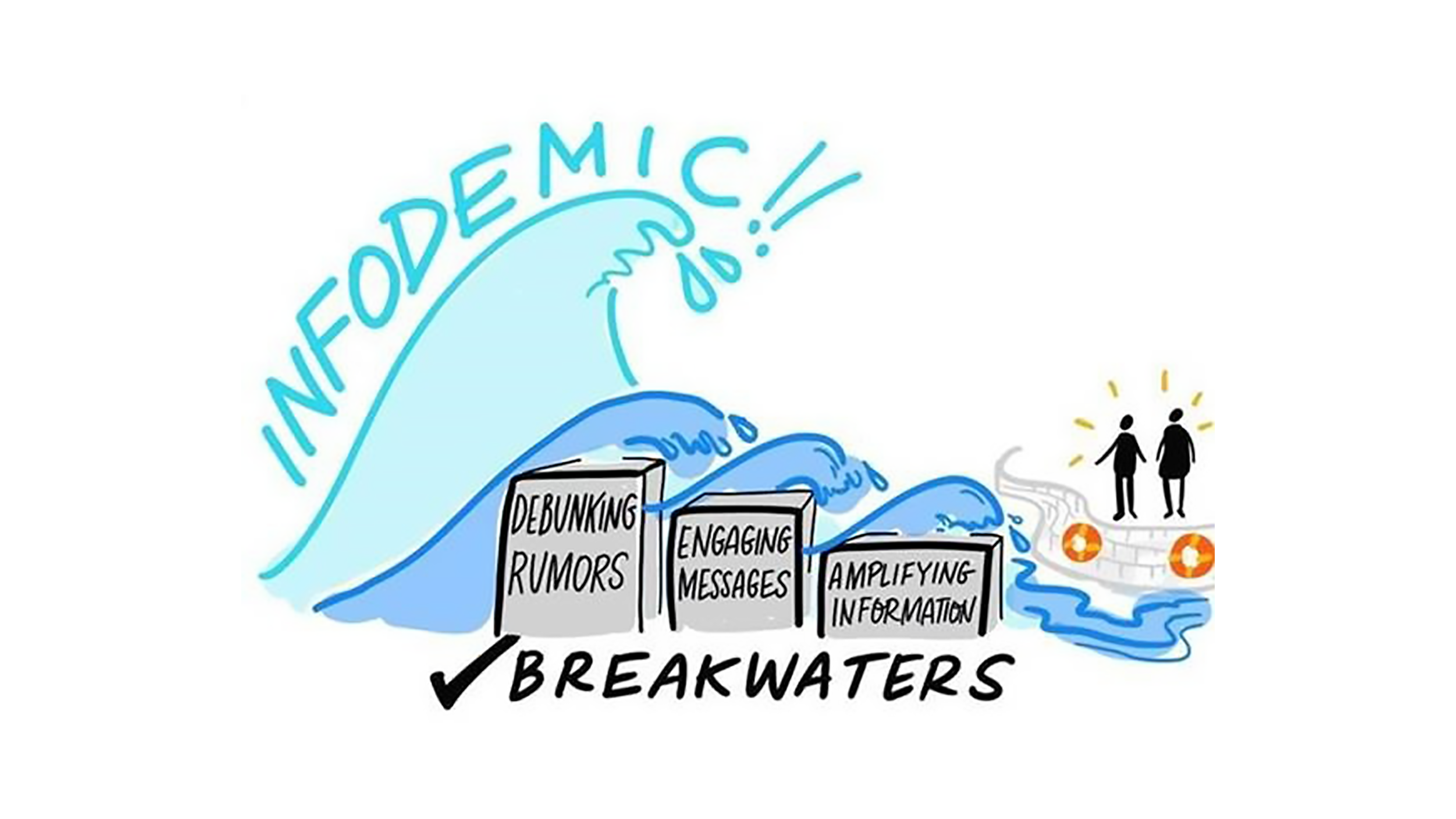

Every day, news about COVID-19 hits us like a tsunami—a wallop of emerging science, public health consensus, rumor, and anecdote, along with some deliberate falsehoods. With misinformation spreading as unpredictably as the epidemic itself, professional communicators—especially those who work in health—have a crucial role to play. Earlier this week, M Booth Health hosted a panel at #PRovokeGlobal, the Global PR Summit, with speakers from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), on how to disseminate information that’s accurate, accessible, and unbiased—and on how to combat misinformation and disinformation.

What is an infodemic, anyway?

Many people were first exposed to the word “infodemic” during this coronavirus but it predates COVID-19. Political scientist David Rothkopf coined the term in a 2003 Washington Post op-ed about SARS, where he wrote that “an information epidemic or ‘infodemic’ has made the public health crisis harder to control and contain.”

For the World Health Organization (WHO), the problem is an overabundance of information—some accurate and some not—occurring during an epidemic. People are consuming so much COVID-19 news in a day that it feels like a week; weeks feel like months, verified reports blend with hearsay and fiction, and it becomes increasingly difficult for people to grasp the most essential facts. Before you know it, you’re in an Onion story: “This Man Hasn’t Heard Or Read A Single True Thing In 6 Years.”

Misinformation can kill

Why would the WHO and other public health experts concern themselves with an infodemic, while a deadly epidemic raged on? Simply put: because information overload is a breeding ground for misinformation, and misinformation can be just as dangerous as the virus itself.

Hundreds of people died in Iran from drinking toxic methanol, erroneously thinking it could cure coronavirus. In the U.S., Americans reportedly drank bleach products to treat the virus. WHO has debunked some of the most common COVID-19 myths, revealing the extent to which information can mutate from person to person. (Spoiler: garlic, hot peppers, and hand dryers CANNOT kill COVID-19, and the ability to hold your breath for 10 seconds DOES NOT mean you are free from the virus.)

Dispelling fiction and disseminating facts

“We’re not just battling the virus. We’re also battling the trolls and conspiracy theorists that push misinformation and undermine the outbreak response,” announced WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in February. Indeed, various organizations (Win Black/Pa’lante, the Malarkey Factory and others) have set up “war rooms” to combat the daily onslaught of online disinformation. Their message: calling out misinformation is everyone’s job.

“Everyone needs to be their own risk manager,” says WHO’s Tim Nguyen. WHO provides this handy guide for how to flag misinformation on each social media platform. Typically, it requires no more than the click of a button.

Truth trumps trolling: tips for communicating complex scientific information

Understandably, the public wants 100%-reliable health guidance when it comes to COVID-19. The problem? Much of the science is brand new and fast-moving. IHME’s Greg Amrofell has several tips for communicators to relay dependable and understantable scientific information to non-scientists:

- Don’t overwhelm In an infodemic, less is more. Break down complex topics with simple statements, data visualization, and video. Amplify your signal, and reduce your noise.

- Check, and re-check your sources Retweets may not be endorsements, but every social media share has power. Communicators can maintain their credibility by getting better acquainted with their sources and only sharing those they know and trust. Check the ownership and potential biases of media outlets and writers on sites like MediaBiasFactCheck and SourceWatch.

- If you don’t know, just say so Be transparent about the uncertainty that’s inherent in the scientific process. The public can handle it.

Turning the infodemic’s tide

WHO’s Tim Nguyen maintains that “we can’t eliminate the infodemic, but we can mitigate and manage it.” Currently, WHO is working with tech giants to prioritize official public health guidance; they’re also developing an emoji that people can use to tag and track misinformation.

Even without fancy tech, everyone (and especially communicators) should pledge to uphold high vetting standards for the information they share online. Earlier this week, the United Nations launched the #PledgetoPause campaign, asking people to pause and think before they click “share.” Doing so might mean you post a little less. But perhaps that’s what’s needed to bring our toxic COVID-19 infodemic under control. Say less, and read more.

#HealthCommunications #Infodemics #COVID19 #misinformation #PublicRelations

Illustration courtesy the World Health Organization (www.who.int)